Reflections from a Baltimore City educator who helped lead a landmark BGE summer jobs program in the late 1960s

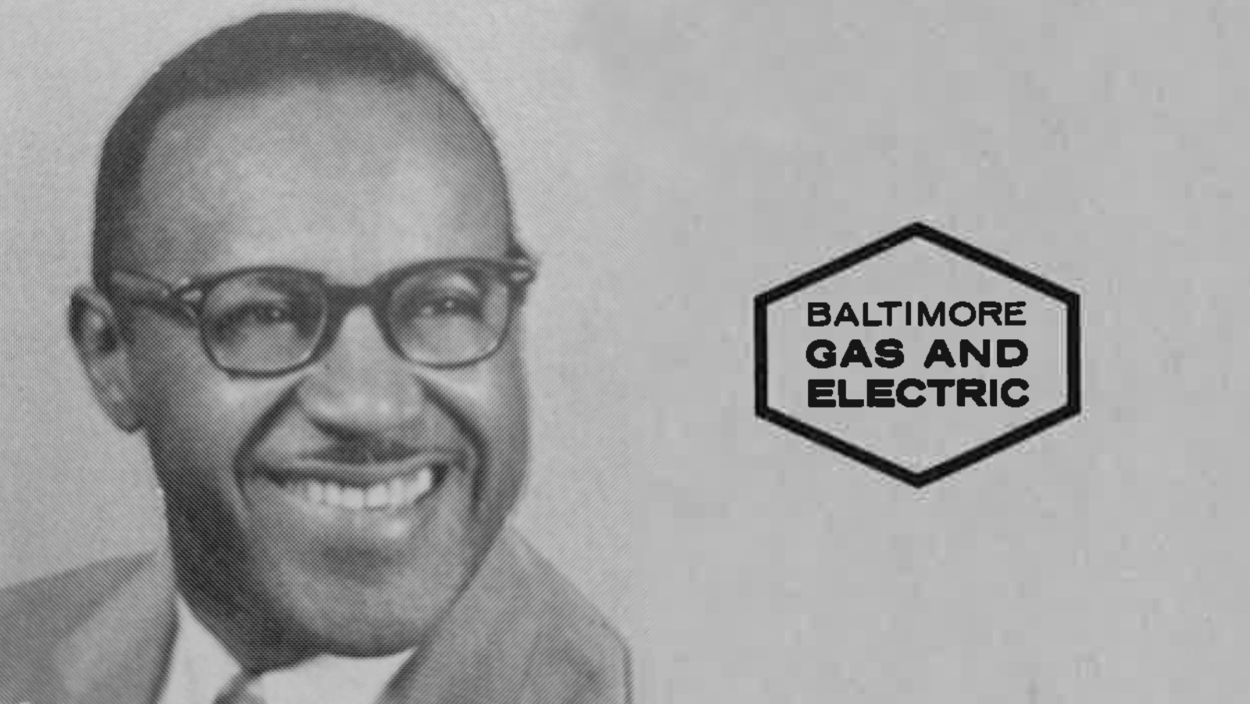

Albert Sinclair Swan was uniquely qualified to mentor young BGE employees.

He had more than two decades of experience as a guidance counselor in Baltimore City high schools, where he also taught English. Born in Bermuda, Swan moved to Maryland’s eastern shore when he was very young. He went on to become an American citizen, a graduate of the Hampton Institute in Virginia, and a high school principal, all before joining the U.S. Navy. He later earned a master’s degree in education from New York University.

A career of extraordinary accomplishment—and, by his own admission, compelled self-censorship. Swan was the first guidance counselor of color hired to serve in a Baltimore City vocational high school (Carver). That was 1946.

Now, as he addressed attendees at the July 1968 BGE quarterly meeting, he finally felt empowered to speak with candor.

“For the first time since childhood,” said Swan when he took the podium, “I have felt free to express an opinion without thought of losing a job. Here is a genuine opportunity for a man to join forces with other men who, like himself, have passed up opportunities to help people less fortunate than himself.”

That genuine opportunity was a new BGE summer jobs program for young adults in Baltimore City. BGE had recently joined the National Alliance of Businessmen, an initiative among large U.S. corporations to hire hundreds of thousands of “hard-core” unemployed people by the early 1970s. Companies also pledged to launch summer jobs programs so hundreds of thousands more from large urban areas would have work experience. BGE brought Swan on board to support the summer employees inside and outside of the office and help supervisors set them up to succeed—for the benefit of the young people who would be employed and for the benefit of the company.

In his remarks at this July 1968 quarterly meeting he provided a lengthy update on the program’s progress and challenges.

Albert Sinclair Swan opened with candor. He closed with a call to action, as follows:

===

Suddenly, gentlemen, business is becoming involved. An article from the Wall Street Journal, a copy of which you will receive, says that Big Business has been dragged, kicking and screaming, into the Civil Rights movement. Business must admit they are equipped to do much in this urban crisis. It will not be easy, “Hard work never was easy” …

George Russell, our City Solicitor, attended school #103. Thurgood Marshall, of the Supreme Court, may well have been Mr. Russell’s neighbor in our inner city for he too is a black Baltimorean, and he too attended school #103.

Cab Calloway graduated from Douglass High School and so did the late Carl J. Murphy, and his father who founded the Afro-American newspaper, a negro business here in the ghetto valued at millions. These and hundreds of others are products of Baltimore City, and all were forced to seek their early education in the inner-city schools and could only graduate from the colored high school. Many of these men washed dishes, portered, waited tables and scrubbed floors as they dreamed. These were the only jobs opened to them.

For the Civil Rights leader and the Negro they represent, one subject overshadows—Jobs. These must be meaningful jobs. Ask a dreamer what kind of a job he would like to have. Should we ask this question this might well be his answer:

I would most like a job that:

Let me live the way I want to.

Let me use my head.

A job that had a fair boss.

That had friendly fellow workers.

A job that was secure.

That gave me a feeling of accomplishment.I would most like a job that:

Let me help other people.

That let me create something new.

Taught me new things.

Let me make beautiful things.

A job that had pleasant working conditions.

Gave me a chance to get ahead.

That paid well.

A job that caused my friends to respect me.Let me conclude with this story from the oratory of the great Negro educator Booker T. Washington in addressing his people. The story is told of a ship at sea. For days the crew had been without drinking water. Their throats were parched. They saw a friendly ship approaching. “Give us water,” they cried. “We die of thirst.” The answer came back from the deck of the passing ship. “Cast down your buckets where you are,” and they did. They dripped up cool fresh water. Little did they dream they were sailing on fresh water.

Friends, we may not be able to bring joy and happiness to the whole world. But we can help 142 inner-city youths this summer. That is what we have pledged to do. Let us cast down our buckets where we are.

===

Swan returned to his position as a guidance counselor at Mergenthaler Vocational Technical High School (Mervo), where he worked until his death in 1972.

Excerpt from “A talk by Mr. A. Sinclair Swan dealing with the hiring of inner city residents under the National Alliance of Businessmen Program,” published by BGE in 1968. Archived material courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Industry.

Photo of A. Sinclair Swan courtesy of Carver Vocational-Technical High School.

More information about BGE’s current workforce development initiatives is available at bge.com.